J’Ouvert in the end, is magic. Wonderful, fantastic, dangerous magic.

J’Ouvert in the end, is magic. Wonderful, fantastic, dangerous magic.

*photo courtesy of the film After Mas, taken by Joseph Mora

J’Ouvert in the end, is magic. Wonderful, fantastic, dangerous magic.

J’Ouvert in the end, is magic. Wonderful, fantastic, dangerous magic.

*photo courtesy of the film After Mas, taken by Joseph Mora

“…many Negroes and Mulattoes the property of Citizens of these States have concealed themselves on board the Ships in the harbor … and to make their escapes in that manner … All Officers of the Allied Army … are directed not to suffer any such negroes or mulattoes to be retained in their Service but on the contrary to cause them to be delivered to the Guards which will be establish’d for their reception …Any Negroes or mulattoes who are free upon proving the same will be left to their own disposal.”–General George Washington, October 25, 1781.

“…many Negroes and Mulattoes the property of Citizens of these States have concealed themselves on board the Ships in the harbor … and to make their escapes in that manner … All Officers of the Allied Army … are directed not to suffer any such negroes or mulattoes to be retained in their Service but on the contrary to cause them to be delivered to the Guards which will be establish’d for their reception …Any Negroes or mulattoes who are free upon proving the same will be left to their own disposal.”–General George Washington, October 25, 1781.

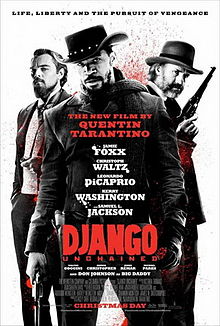

Django Unchained, director Quentin Tarantino’s ode to 1970s Blaxploitation flicks and the famed Italian spaghetti westerns of the same name, tells the story of the freed slave Django (Jamie Foxx) who goes on an orgy of revenge killings to rescue his wife Brunhilda (Kerry Washington) from her sadistic owner. Set in the American South two years before the Civil War, Django (though in many ways a western) is rooted in slavery–it is the film’s backdrop, the driving force behind the plot and what creates both heroes and villains of its main characters. Yet the slavery of Django bears only a passing resemblance to the slavery of our national past. Rather, it is the slavery of popular folklore, social mythology and age-old Hollywood caricatures–the slavery of our imaginations.

Django Unchained, director Quentin Tarantino’s ode to 1970s Blaxploitation flicks and the famed Italian spaghetti westerns of the same name, tells the story of the freed slave Django (Jamie Foxx) who goes on an orgy of revenge killings to rescue his wife Brunhilda (Kerry Washington) from her sadistic owner. Set in the American South two years before the Civil War, Django (though in many ways a western) is rooted in slavery–it is the film’s backdrop, the driving force behind the plot and what creates both heroes and villains of its main characters. Yet the slavery of Django bears only a passing resemblance to the slavery of our national past. Rather, it is the slavery of popular folklore, social mythology and age-old Hollywood caricatures–the slavery of our imaginations.

A lengthy post for a lengthy film. As always, spoilers.