“De only Ku Klux I ever bumped into was a passel o’ young Baltimore Doctors tryin’ to ketch me one night an’ take me to de medicine college to ’periment on me. I seed dem a laying’ fer me an’ I run back into de house. Dey had a plaster all ready for to slap on my mouf. Yessuh.”

—Cornelius Garner (ex-slave, Virginia), interview by Emmy Wilson and Claude W. Anderson, May 18, 1937 (Weevils in the Wheat, 1976:102)

Image: Actor, Rapper, Artist Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def) featured on a cover for his 2004 album, The New Danger–one of many visual inspirations for the enigmatic Dr. Antoine Bissett. A fellow boogie man.

So begins my short story “Night Doctors” which tells the story of Dr. Antoine Bissett, a Black physician in the 1930s who finds himself in Durham, North Carolina for the Works Progress Administration–ostensibly to collect the life stories, folklore, testimonies, and memories of the last remaining ex-slaves in the United States. In reality, Dr. Bissett has come seeking much more–the source of hate as a darkness that infects mankind that will forever change his life.

“Night Doctors” was originally published in the anthology Nowhereville out out by Broken Eye Books in 2019, and reprinted in NIGHTMARE magazine in 2020; it has even become an audio in the anthology Stories to Keep You Up Night produced by Realm media. Still, it’s mostly flown under the radar. And each time it’s republished, I get messages from readers surprised to come across it–as it is currently the only other story set in the same canonical universe as my novella Ring Shout.

Imagine my surprise then, this weekend, randomly stumbling across a blog post in Reactor (the artist formerly known as Tor) magazine titled, “The Price of Research: P. Djèlí Clark’s “Night Doctors.” And from 2022! Say what? I rarely read reviews. Like, write your heart away at Goodreads and say whatcha like. I’m very appreciative. Please keep writing them! Honestly, that anyone takes the time to review something I rote, how can I not be appreciative? Even if you got critiques. But for my own sense of self, I don’t often read em’. And I don’t get angry at anyone for writing a negative review (that’s part of this life) …unless you tag me in your bad review. Then I’m blockity-blocking you into the Phantom Zone. Because why even do that…weirdo.”

Anyway, I don’t often read reviews–but I am intrigued by really critical takes. And “The Price of Research” analyzing “Night Doctors” goes IN! The authors are story writers Ruthanna Emrys, who is also a trained behavioral scientist, and Anne M. Pillsworth. They bring their own backgrounds as experts of writing, horror, science and more to their analysis. Reading it, I found I couldn’t stop. It had me thinking of things I hadn’t even thought of regarding my own story.

And it inspired me to write this blog.

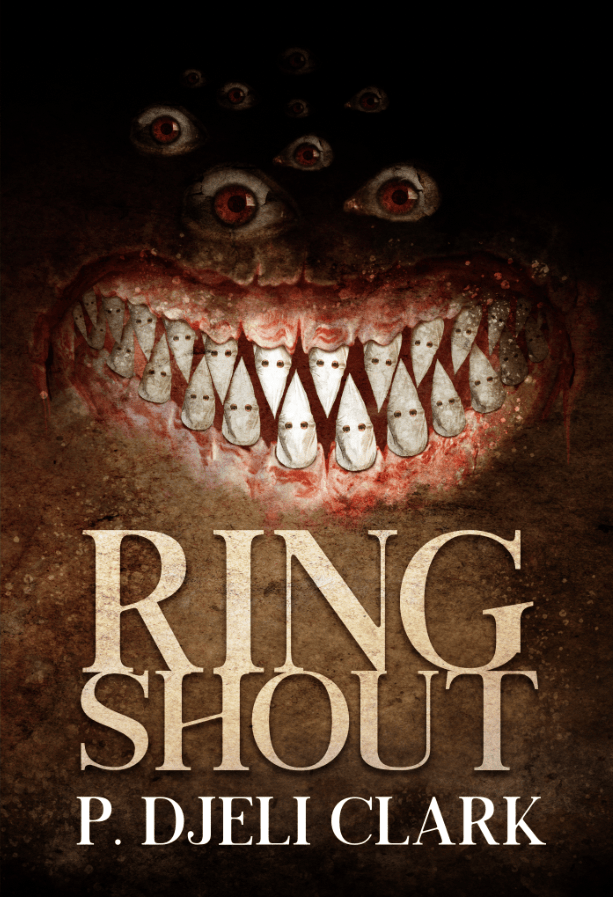

Most readers familiar with my work were introduced to Dr. Antoine Bissett and Night Doctors from my 2020 novella Ring Shout–which follows three heroines fighting monstrous creatures called Ku Kluxes in1920s Georgia, and the human hate that allows them to thrive. Dr. Bissett was a side character, though certainly a memorable one as readers have expressed to me over the years. “Night Doctors” the short story, was thus a welcome prequel–offering an origin story for Dr. Bissett. But, from the dates I’ve just given, some of you are likely now asking, “but wait–didn’t Night Doctors come before Ring Shout?” And the answer is, yes. In fact, it was the inspiration.

Here, let me explain….

A long time ago, back when I was working on my first M.A. degree in history, I became fascinated by the ex-slave narratives found in the WPA (Works Progress Administration) collected mostly during the 1930s. As part of a way of finding employment for citizens during the Great Depression, the United States government paid field agents and researchers to go out and collect the voices, histories, and cultures of America–creating a dazzling archive now held primarily by the Library of Congress. Among these were interviews of formerly enslaved people still alive in the 1930s, some 70 or more years since slavery had ended with the Civil War. The WPA’s interest in ex-slave accounts was itself inspired by work conducted by earlier Black researchers in the 1920s, including the author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston and historically Black colleges like Fisk University. These pioneering efforts were joined to the data collected by WPA workers, Black and white, men and women, and became part of the larger Ex-slave Narrative Archive still housed by the Library of Congress, which includes printed interviews, photographs, recordings, and more.

The archive itself, has not been without controversy. By the time of the WPA interviews most former slaves in the United States were elderly men and women. It was feared that old age had impaired recollections of slavery. Further, most interviewees were children or adolescents whose experiences of slavery were brief. Many were recalling memories of enslavement during their childhood, or accounts passed on to them by parents and older adults. Most were also living in extreme poverty as a result of the Great Depression and compounded by racism, causing some to recall a more benign slave era. Or through the rose-colored glasses of childhood. Added to this, the WPA sometimes hired white interviewers who expected formerly enslaved people to observe the Jim Crow etiquette of the time, including the rosy Lost Cause narratives of slavery. Some white interviewees were even descendants of their past owners! Or were connected to the families on whose land formerly enslaved people still lived and toiled with their families as sharecroppers. Unsurprisingly, some ex-slaves, long skilled at the survival tact of dissembling, offered up images of slavery which they reasoned white interviewers wanted to hear. Tellingly, these were sometimes followed up by inquiries of whether they might be compensated or gifted with money for their time, and a lamenting on their dire economic circumstances.

Some historians worried openly that the narratives might cause more harm than good, and shied away from their use. This wasn’t without reason. None other than the white supremacist shooter and mass murderer Dylan Roof who opened fire on Black church goers in 2015, cited the WPA narratives–claiming that he’d read “hundreds” and they showed that slavery was actually a good thing, and that white people had been made to feel needlessly guilty.

But, the ex-slave narratives are actually far more complex. As scholars have long noted, the race of the interviewer directly affected how former slaves responded to questions. White interviewers tended to get far more favorable reviews of slavery than Black interviewers. Even some Black interviewers, considered strangers who might perhaps carry water for whites, were sometimes not trusted. In one instance, a former slave began recollecting cheery accounts of slavery to a Black interviewer–until her frustrated daughter intervened and demanded her mother show the interviewer her back. Chastened, the formerly enslaved elderly woman did so–revealing the terrible scars from countless whippings. Almost instantly her demeanor changed, and she began to tell nightmarish stories of abuse, degradation, and violence.

In more recent decades, the archives have been much more accepted and used. Historians who do so talk about things like “reading between the lines” or taking the context of who the interviewer was. Others speak of simply recognizing that these were human beings who had endured unspeakable trauma, and who may have simply been unwilling (perhaps even unable) to voice them openly to strangers. Some memories may have been too painful to revisit or eved hidden away by a victim’s own psyche to spare them the agony of remembrance.

For me, the archives were quite useful. My M.A. thesis explored enslaved women who used violence to resist slavery—from fighting back, to beating down their white “mistresses,” to chopping up overseers and “masters” alike. The narratives also offered plenty of evidence of shocking violence and abuse committed under slavery–an overwhelming amount in comparison to the very less numerous cases that painted benign images of slavery. It turns out the devil is a liar. And so is Dylan Roof. But I repeat myself.

The thing is, when you go through some of the ex-slave archives, you never know what you might find. I was just looking for stories of enslaved women who used physical force to resist their bondage. I was not expecting to also run into lots of folklore. Two in particular stood out to me. One involved stories of the first Klan. Founded by ex-Confederate soldiers in 1866, including Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest, this initial KKK operated as an insurgent terrorist group–too afraid to take on the Union army that had just defeated them, so instead taking out their cowardly acts of brutality, sexual assault, and violence on ex-slaves and any who aided them. WPA interviewers had lots of questions about this first Klan, perhaps because they had lived through the rise of the Second Klan in the wake of Lost Cause pro-Klan film, The Birth of a Nation (1915)–which had essentially revitalized the then mostly defunct Klan, swelling its ranks to near 4 million and spreading to nearly ever part of the country.

Former slaves interestingly described this first Klan using folkloric language: that they wore horns and chains; that they were haints (wicked spirits); or that they performed supernatural acts like drinking gallons of water, because they had just returned from Hell. Even the methods of stopping them were couched in folklore: shoveling hot ash into their faces or laying vines out on the road which (like Nazgul and flowing water) their horses could not cross. Of course, ex-slaves knew these Klan members were just people; many likely knew exactly *who* they were, whether former owners or well-known figures in town. But they used the supernatural and folkloric perhaps as a way to express their trauma–making real monsters of those who would commit monstrous acts.

One of the other bits of folklore that caught my notice, was that of Night Doctors. These showed up in a few narratives, including the quote I started this blog with. In these bits of folklore Night Doctors (or Night Witches, Bottle Men, etc) were monstrous beings who stole away enslaved people in order to perform experiments on them. The origin of these stories has been explored by scholars and folklorists alike. Some trace the first Night Doctors to slave owners, who created the story to keep their enslaved populace in line–some perhaps even going as far as dressing up to play the part. Others, surmise that it came from many of the real life horrors of slavery: medical experiments conducted on enslaved men, women, and children (more common than many realize) or the grisly practice of selling the bodies of deceased enslaved people to local medical colleges seeking fresh cadavers. At times, Night Doctors even appear to become mingled with other figures of Black oppression–so that they, slave patrollers and the Klan at times blur into one unrelenting white horror. Whatever their origins, Night Doctors survived past the slave era, and traveled along the migration routes of Black Southerners, perhaps taking on new roles that helped explain traumas like the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments or the ever-lingering medical apartheid endured by Black patients to this very day.

I was so taken by both of these bits of African American Southern folklore, that I jotted them down, saving them in a side folder during my own M.A. thesis work. Back then, I hadn’t even really started writing speculative fiction–at least not seriously. But I knew that somehow, someway, I wanted to do something with this folklore. I wanted more people to know about them. To learn about these buried parts of history and the way enslaved and formerly enslaved people created complex stories and folklore to express the horrors that beset them. I could have opted to do something academic–a journal article or conference perhaps. But, I wanted to honor them through storytelling, which is the way, after all, they had been passed down.

It would take me almost 15 years until I was ready to write those stories. I hadn’t forgotten about monstrous Ku Kluxes or Night Doctors. I just couldn’t ever find the right way to tell the story, in a way that did them justice. It beez like that sometimes. The story will get written when it’s good and ready–and so are you. Then, sometime around 2012 to 2013, I got the kernel of an idea for the Night Doctors. I didn’t start writing right away. Instead, I kept dreaming up how I could tell it, going through different scenarios, perspectives, and plots. Then in 2015/2016 NIGHTMARE magazine announced calls for submissions for a special edition called People of Colo(u)r Destroy Horror! My time had come! I had just finished my PhD and finally had time to write SFF again. I wrote “Night Doctors” in about two weeks. This version all but abandoned all my earlier ideas, and instead decided to take inspiration from the WPA narratives–creating a main character named Dr. Antoine Bissett and making him an interviewer. Pulling on quotes and elements directly from several narratives, I incorporated the Night Doctor folklore into a new tale. And I also decided to go very cosmic horror with it, giving my own spin to their motives. I submitted my story to People of Colo(u)r Destroy Horror! …and it didn’t make it. Hey, rejections is just part of the game if you wanna get into this biz. I was disappointed. But I was heartened to learn from one of the editors that the story had made it to the shortlist.

Then I mostly kinda put it to the back burner. I was getting ready to move to Connecticut to start up life as a junior tenure-track scholar. I had classes to prep for. I had a dissertation manuscript I needed to start thinking about shaping into a book, and finding an academic press. And in my SFF writing life, my recently published novelette “A Dead Djinn in Cairo” was doing surprisingly well. So much so, I was wondering if I should write more in that world…. Narrator’s voice: he did.

I might have forgotten about “Night Doctors” all together if editor Scott Gable hadn’t contacted me in late 2016. He’d read “A Dead Djinn in Cairo” and then some of my blog posts, and wanted to know if I was open to submitting to an anthology with his indie press. Turns out, I didn’t have a story for that anthology, so he asked about a next one called Weird in the City. But I was really busy by this time not just with scholarly life, but editing a new novella I’d just finished called The Black God’s Drums and sending another one off to my new editor at Tor (the great Diana Pho) called The Haunting of Tram Car 015. I apologized to Scott that I didn’t have the bandwith for anything new. BUT, I did have this weird short called “Night Doctors.” He read it and loved it–but it didn’t fit his current anthology. However, he said it might fit his next one, Nowhereville. And yadda, yadda, yadda… the rest is history.

Now, the reality is, “Night Doctors” still wasn’t on most folks radar. It got a few nods and mentions, but largely went unremarked. Most people around this time were associating me with steampunk alt-history or magical vignettes about George Washington’s teeth–not horror. Or Southern gothic hauntings.Then in 2020, I finally published a story that got to incorporate that other bit of folklore I’d held onto from the WPA Narratives–the notion of Klan members as monsters. Ring Shout, which came out in October 2020, was more popular with readers than I ever possibly conceived. Somehow it arrived right on time–in the midst of HBO’s adaptation of Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country, a real world global pandemic, and the powerful George Floyd protests. Something about that moment made the story speak to reader. And (for the first time) some learned about “Night Doctors”–and met the enigmatic Dr. Bissett.

How that happened is a big convoluted. As early as 2015, I had started thinking of how to use the folklore of Klan monsters first gleaned from the WPA narratives some ten years previous. I didn’t have a story, but I had ideas! And everything from Beyoncé’s “Formation” video to the MacIntosh County Shouters to long drives through the misty mountains of Pennsylvania (Old Gods of Appalachia anyone? ) while on a teaching fellowship, served as inspirations. But I didn’t pitch it as a possible story until March of 2019. And I didn’t actually sit down and write it in a dizzying four weeks, until August of that year. When I did, I already had “Night Doctors” completed and under my belt. But somehow, I wanted Dr. Bissett and the Night Doctors to be in there. I remember pondering how to do this. I grew up on comic books where the crossover was common–I lived for them! But in a book? Bringing in characters from an entirely different story? Was that allowed? How would I do it anyway? Ring Shout was set in the 1920s and “Night Doctors” the 1930s. There was a whole time discrepancy where Dr. Bissett is meeting people from his past, before he’d even met the Night Doctors. Then I remembered that story has a giant friggin’ monstrous centipede and a tree that bleeds—and said, “I can do whateva the hell I like.”

And I did.

Dr. Bissett and the Night Doctors crossed over into the world of Ring Shout, and it was perfect. Best writing decision I ever made.

Anyway, so that’s how these two stories happened–out of sync and out of time, and yet just right. Both owe to African American Southern folklore and the ex-slave narratives collected for the WPA. And I hope both give readers hints at some of our past and inspire them to learn more about how it all still impacts our present.

If you get a chance, do read the original “Night Doctors” if you haven’t. And if you haven’t checked out that article from 2022 in Reactor magazine that really takes a deep dive into the tale, its meanings, and history–I highly recommend it.

But keep the lights on. There are monsters.